General information on risk assessment

In order to assess risks in the areas of health, food safety and consumer protection and subsequently minimize them, our experts follow the principles of risk analysis. This is a process consisting of the interconnected individual steps of risk assessment, risk management and risk communication. Our core task, especially that of the Integrative Risk Assessment, Data and Statistics department, is to assess and communicate risks along the entire food chain and to make recommendations for risk management.

The aim of risk assessment is to identify and quantify health hazards that may emanate from food at an early stage in order to be able to estimate the associated outgoing risk to humans, animals and plants. In terms of preventive protection of consumers, the hazards and the risks they pose are minimized.

We conduct risk assessments to answer the following questions:

- What can happen (hazard)?

- What can make it happen (causes, triggers)?

- How bad can it be (extent of damage)?

- How likely is it to happen (probability)?

- What recommendations can be derived from the risk assessment for risk management?

- What measures can risk management take?

- What is the effect of these risk management measures?

- Would the collection of more data influence the risk management decision?

- Would incorrect assumptions change the risk management decision? If so, is this testable?

- What is the cost if measures are implemented? What is the cost if no measures are implemented? Who incurs these costs?

Steps of the risk assessment

Risk assessments are carried out on the basis of the latest scientific findings and must be transparent, objective and comprehensible. In both Regulation EC178/2002 and the Health and Food Safety Act (GESG), risk assessment is defined as a science-based process involving four stages: Hazard identification, hazard characterization, exposure assessment and risk characterization.

Step 1 of the risk assessment - The hazard identification.

The first step, hazard identification, involves determining the origin of the hazard, how it is formed, and the route by which it is introduced into the food. Hazards can be of many types. They are divided into biological (microorganisms such as salmonella, listeria), chemical (pesticides, veterinary drugs, heavy metals, etc.) or physical hazards (foreign bodies such as stones, glass). These hazards can be introduced into or created in food in the course of agricultural production, environmental pollution, food processing, and also food preparation in the home. Natural food ingredients and additives also have the potential to cause undesirable health effects.

Step 2 of the risk assessment - Hazard characterization

In the hazard characterization step, the hazard is described in more detail and assessed qualitatively and quantitatively. Data from scientific research, toxicological studies, epidemiological studies and statistics are used. Hazard characterizations carried out nationally and internationally are also taken into account, provided that they have been carried out in accordance with the specifications on a scientifically sound basis in a transparent and traceable manner. This can result in toxicological indicators such as the ADI (acceptable daily intake) or TDI (tolerable daily intake). These indicate the amount of a substance that can be ingested daily over a lifetime without causing adverse health effects.

Step 3 of the risk assessment - The exposure assessment

During the exposure assessment, the total current exposure to a particular pollutant within a defined population is considered. It is often necessary to consider separately the exposure of specific population groups, such as children, as they are a particularly sensitive group and may be more highly exposed to certain substances than adults (e.g., patulin in apple juice). Exposure assessment is based on linking consumption data of specific foods with the presence of the substance in the affected foods. All relevant components have to be included: Occurrence and concentration in different foods and feeds, possible transfer effects to foods of animal origin, influencing factors during storage, processing or preparation. In addition, it is necessary to consider all sources of exposure. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons , for example, are absorbed by humans not only through food, but also through the atmosphere and cigarette and tobacco smoke.

Example: Exposure to mercury within the Austrian population can be estimated from mercury levels in food and the amounts consumed of these foods.

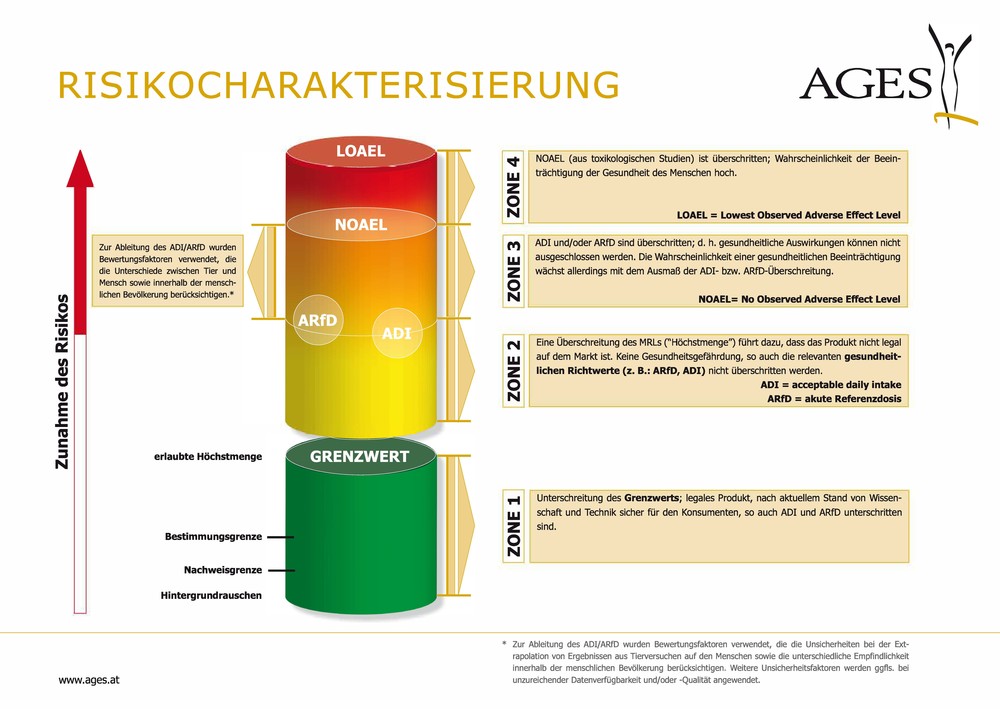

Step 4 of the risk assessment - Risk characterization

All data and information from the first three steps are now used for the risk characterization in order to quantify the health risk for humans. As far as the state of knowledge and the data material allow, statements are made on the probability, frequency and severity of known or potential adverse effects on human health, taking into account all uncertainties that have arisen in the course of the risk assessment.

Proposals for risk management

The risk assessment produced results in risk management proposals such as maximum content proposals for certain foods. Risk management is necessarily located in the regulatory sphere such as the federal ministry and state government. The proposals are used by risk management as a basis for regulatory action. Social, economic, environmental and ethical aspects are also taken into account.

Taking all these aspects into account, measures are set (regulations, restrictions of use, prohibitions of use, recommendations) to minimize the exposure of the population to undesirable substances and to ensure the highest possible food safety.

Risk communication

At each stage of risk assessment, there should already be intensive communication between all those involved in the process. Effective risk management requires a permanent dialogue and exchange of information between risk assessors and decision-makers, involving other scientific bodies, affected economic groups, interest groups and consumers. Special attention must be paid to risk communication to consumers. It should be carried out in an open, transparent and clearly understandable manner.

Contaminant

A contaminant is any substance that is not intentionally added to the food. However, it is present in the food as an undesirable substance. Contaminants occur in the environment, are created during production, processing, transportation or storage, and during household food preparation.

Process contaminant

Process contaminants are substances that form in food or food ingredients when they undergo chemical changes during processing. Food processing operations include such things as fermentation, smoking, drying, refining, and heating at high temperatures. Examples: Acrylamide, furan, 3-MCPD, PAHs.

Plant & mold toxins (agricultural contaminant)

Plant and mold toxins are naturally occurring toxins in plants and molds.

Mold toxins (mycotoxins) are metabolic products from molds that can be toxic in even the smallest amounts. They can be formed, for example, in grain during bad weather or during food storage. Examples: Aflatoxin, fumonisins, ochratoxin A, deoxynivalenol.

Plant toxins are natural poisons of plants, which they use to protect themselves from predators. There are very many different substances with varying degrees of toxicity. The toxins can get into the crop during harvest or be detected as by-products when harvesting vegetables or tea, for example. Examples: Pyrrolizidine alkaloids, tropane alkaloids, morphine, hydrocyanic acid.

Environmental toxin (environmental contaminant)

Environmental contaminants are substances that occur naturally in the environment or are released into the environment by industrial processes. Consequently, they can enter the food chain and thus food as undesirable substances via water, soil and air. Examples: Heavy metals, dioxins, persistent organic pollutants.

Backlog

Residues usually remain as residues of deliberate application on or in food (plant protection products, veterinary drugs).

Plant protection products

Plantprotection products or pesticides are substances used to protect useful and ornamental plants from diseases, pests or weeds. Plant protection products are subjected to extensive scientific testing before they are approved. In accordance with Regulation (EC) No. 396/2005, an annual testing program is carried out on plant protection product residues in food and feed.

Veterinary medicinal products and hormones

Veterinary medicinal products and hormones are substances used to protect the health of farm and domestic animals. The active substances used must be comprehensively checked before they are approved. On the basis of the national residue control plan, the lawful use of approved veterinary medicinal products is checked. Further objectives are the detection of illegal use of prohibited or unauthorized medicinal products. In addition, the exposure to various environmental contaminants (e.g. heavy metals, dioxins) is recorded.

Danger and risk

A hazard is the ability of a biological, chemical or physical agent to adversely affect health. This can be a biological, chemical or physical agent in a food or feed, or a condition of a food or feed. For example, a bacterium, a toxic substance, or a piece of glass may pose a hazard.

The risk of an adverse health effect is composed of the probability of occurrence and the severity of that effect as a consequence of the realization of a hazard.

In contrast to the qualitative concept of hazard, risk is a quantitative concept that describes the magnitude of a hazard. Risk-based considerations are the foundation of any modern monitoring activity. The presence of a hazard does not automatically imply a health risk for humans.

Exposition

Exposure describes the degree to which a person is exposed to certain pollutants. These include synthetic chemical and natural pollutants, radiation, or bacteria.

Major types of exposure:

- Oral exposure: ingestion through the diet, e.g., arsenic through contaminated rice.

- Dermal exposure: uptake through the skin, e.g. aluminum in cosmetics.

- Inhalation exposure: uptake via respiration, e.g. pollutants through smoking

Endocrine active substances

Endocrine active substances are substances that can influence or disrupt the hormone activity of the body. If this leads to adverse health effects, they are referred to as endocrine disruptors (or endocrine-disrupting substances). They can occur both as residues and as contaminants.

Regulatory terms

This is a quantity of a substance in/on food, above which it is necessary for food businesses and authorities to identify the cause and take action to reduce it. An action value does not represent a "limit" or maximum level. Action values can be set at EU level or nationally.

Example: microorganisms in drinking water, aluminum in pretzels

Das Frischgewicht ist das Gewicht eines Lebensmittels in frischem Zustand inklusive seinem natürlichen Wassergehalt. Die Angabe ist wichtig, da sich Gewichtsangaben von Lebensmitteln im frischen Zustand von jenen im getrockneten sehr stark unterscheiden. Viele Höchstgehalte an Schadstoffen in Lebensmitteln beziehen sich auf das Frischgewicht. In speziellen Fällen wird als Bezugsgröße das Trockengewicht (getrocknete Probe, enthält nur noch geringe Mengen Wasser) oder die Trockensubstanz (Probe ohne Wassergehalt) herangezogen.

Toxicological key figures

The ADI is the amount of a substance that, according to current knowledge, can be ingested daily over a lifetime without posing a health risk to humans. It concerns substances that are added to food during production or processing, such as additives or pesticides. The ADI is a guideline value for health.

The TDI is the amount of a substance that, according to current knowledge, can be ingested daily over a lifetime without posing a health risk to humans. It concerns substances that enter the food via the environment or during processing, or that are formed during the processing of the food, such as 3-MCPD. The TDI is a health-related guideline value.

- Limit of detection (NG, LOD= limit of detection): A specific limit in chemical analysis above which the presence of a substance in a sample can be detected, but not quantified with sufficient certainty.

- Limit of quantification (BG, LOQ): A specific limit in chemical analysis above which the quantity of the substance can be determined with sufficient certainty.

Statistical key figures

The data come from random samples. The statements of the results are therefore subject to a certain uncertainty - the true value lies within the CI with a probability of 95%. The width of the interval depends largely on the number of data. The more data/samples available, the narrower the CI, or the fewer data/samples available, the wider the CI.

Therefore, a complaint rate of 21% with a CI of 13 to 23% means that 21% of the samples were rejected. However, the complaint rate can also take any value between 13 and 23%. The complaint rate can only be given more precisely if more samples are examined.

More information

Important technical terms used in risk assessment, such as ADI, TDI, exposure, etc. are explained in EFSA's scientific glossary in different languages.

Last updated: 23.09.2024

automatically translated