Foodborne disease outbreaks

Consumers expect hygienically safe food and the food industry attaches great importance to the quality of its products. If people nevertheless fall ill as a result of eating food contaminated with pathogens, an attempt should be made to find out the causes.

In individual cases, it is usually not possible to find the cause of the disease in the variety of foods consumed. However, in group illnesses, known as foodborne outbreaks, there is a better chance of finding the food that served as the transmission vehicle for the pathogen by working out characteristic similarities between cases.

Definition: a foodborne outbreak is defined in the Zoonoses Act 2005 as follows: The occurrence, under given circumstances, of a disease and/or infection associated or likely to be associated with the same food or food business in at least two cases in humans, or a situation in which the cases detected are more prevalent than expected.

Situation 2023

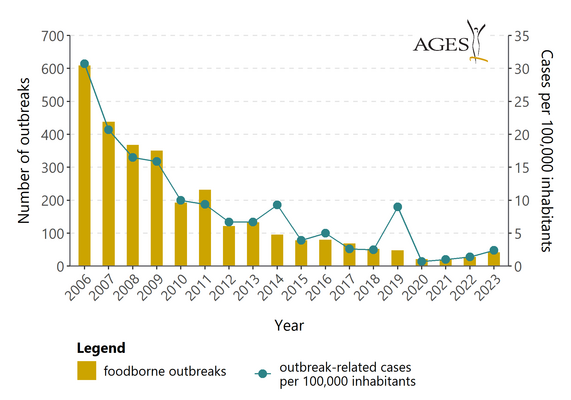

A total of 42 foodborne outbreaks were reported in 2023, 14 more than in 2022. 222 people were affected by the outbreaks in total, almost twice as many as in 2022 (128 people), but significantly fewer than in 2019 (793 people) in pre-coronavirus times. 38 people had to be hospitalised in connection with the outbreaks (2022: 57, 2021: 27, 2020: 17, 2019: 159); there was one death (2022: 4 deaths, 2021: 2 deaths, 2020: no deaths, 2019: one death). The average number of people per outbreak was 5.3 and affected between one and 32 people in each outbreak. This individual is attributable to a transnational outbreak that had already started in 2022. Again, the number of household outbreaks in 2023 is higher (n = 25) than that of general outbreaks (n = 15), and there were also two outbreaks of unknown status.

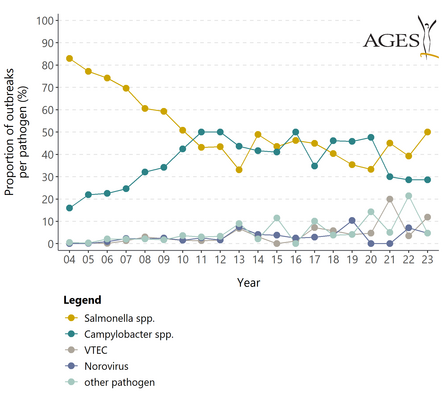

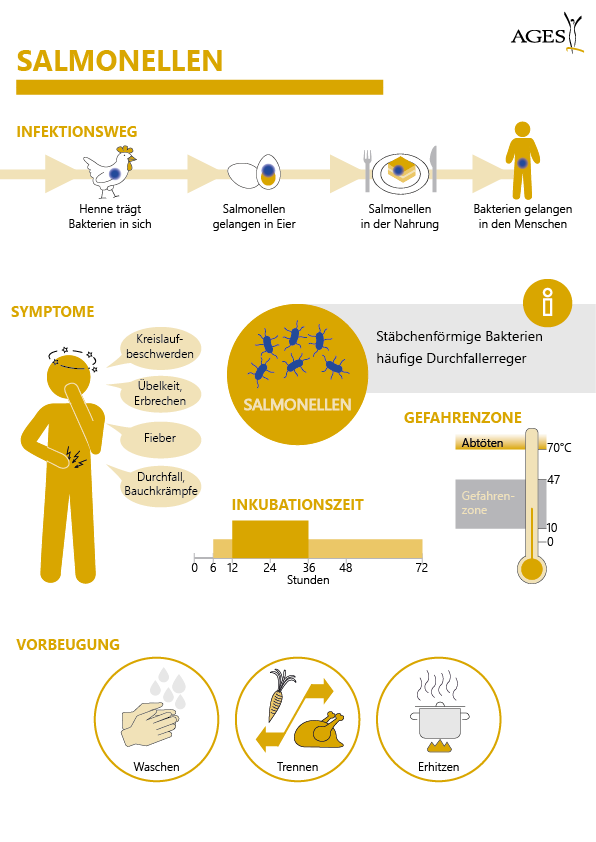

Salmonella was the most common outbreak agent (21 outbreaks, 141 people affected, one death). Campylobacter is in second place (12 outbreaks, 26 cases), followed by five outbreaks caused by STEC (12 people), two outbreaks caused by norovirus (138 people) and one each caused by Listeria monocytogenes (3 people) and Yersinia enterocolitica (2 cases).

Three major foodborne outbreaks in 2023 were caused by three different clusters of Salmonella Enteritidis ST11 (CT9791, CT13755, CT2114), with 31 people falling ill in Austria, 10 of whom had to be hospitalised; one patient died. A total of 335 cases occurred in 14 EU countries, the UK and the USA. The contaminated food was chicken kebab with meat from a farm in Poland(European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, European Food Safety Authority, 2023. Three clusters of Salmonella Enteritidis ST11 infections linked to chicken meat and chicken meat products - 26 October 2023)

One outbreak with strong evidence - caused by L. monocytogenes Sg IVb/ST6/CT90 - affected three people, two of whom had to be hospitalised. The responsible food product was cooked pork bacon from an Austrian producer.

A foodborne outbreak from 2022 (four people were affected) continued in 2023 with one person. The pathogen found was Salmonella Senftenberg ST14 CT17028 and the infections were caused by eating tomatoes from Morocco(European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, European Food Safety Authority, 2023. Multi-country outbreak of Salmonella Senftenberg ST14 infections, possibly linked to cherry-like tomatoes - 27 July 2023)

An important outbreak with strong evidence was a multi-country outbreak caused by Salmonella Strathcona ST2559 CT3910 and affected 24 people, four of whom had to be hospitalised. A total of 149 cases occurred in 9 EU countries, the UK and the USA. The suspected foodstuffs were cherry tomatoes from a farm in Italy(European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2023. Communicable Disease Threats Report. Week 46, 12-18 November 2023. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023).

A particularly high number of outbreaks in 2023 are associated with stays abroad (10 outbreaks caused by Salmonella, 5 outbreaks caused by Campylobacter).

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food-borne outbreaks | 609 | 438 | 368 | 351 | 193 | 232 | 122 | 133 | 96 | 78 | 80 | 69 | 52 | 48 | 21 | 20 | 28 | 42 |

| - of which due to salmonella | 452 | 305 | 223 | 208 | 98 | 100 | 53 | 44 | 47 | 34 | 37 | 31 | 21 | 17 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 21 |

| - of which due to Campylobacter | 137 | 108 | 118 | 120 | 82 | 116 | 61 | 58 | 40 | 32 | 40 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 12 |

| Number of cases (in connection with foodborne outbreaks) | 2.530 | 1.715 | 1.376 | 1.330 | 838 | 789 | 561 | 568 | 790 | 333 | 436 | 227 | 222 | 793 | 67 | 92 | 128 | 222 |

| - Infected persons per 100,000 inhabitants in connection with outbreaks | 30,7 | 20,7 | 16,5 | 15,9 | 10,0 | 9,4 | 6,7 | 6,7 | 9,3 | 3,9 | 5,0 | 2,6 | 2,5 | 9,0 | 0,7 | 1,0 | 1,4 | 2,4 |

| - of which treated in hospital | 493 | 286 | 338 | 223 | 155 | 179 | 97 | 108 | 121 | 86 | 68 | 56 | 58 | 159 | 17 | 27 | 57 | 38 |

| - Number of deaths | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

Types outbreaks

Based on the Austrian Zoonoses Act, we collect outbreak data annually and forward it to the EU. Certain classifications result for this reporting: Outbreaks in which only members of a single household are affected are categorized as a household outbreak. If individuals from multiple households are affected, this is counted as a general outbreak. Household outbreaks account for the majority (approximately 75%) each year because it is often not possible to epidemiologically link cases of illness from different household outbreaks by identifying a single causative food.

Outbreak clarification

The aim of the outbreak survey is not only to stop the outbreak that is currently taking place, but above all to prevent such diseases in general in the future.

Detailed and systematic searches can succeed in locating both the infectious vehicle, that is, the food that transmitted the infectious agent to humans, and the reservoir, which is the habitat in which an infectious agent normally lives. Only then is it possible to set targeted and meaningful interventions. These measures should result in the elimination of the outbreak cause, namely the infectious agent, from the food chain and consumers are no longer exposed to this agent.

The following historical example illustrates the preventive medical potential of an outbreak investigation: In July 2004, it was possible to clarify a foodborne outbreak caused by Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 36, a very rare Salmonella type in Austria, which affected 38 people in four provinces, and trace it back to a flock of laying hens. The flock was eradicated, the farm thoroughly cleaned and disinfected; subsequently, new laying hens were housed. As a result of these measures, not a single further case of illness caused by Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 36 has been reported in Austria since then.

Since 2009, bacterial and viral foodborne infections and poisonings have been reported via the EMS, an area-wide surveillance system. However, these reporting figures must be viewed in a nuanced manner: Numerous factors can lead to an underestimation of the actual illness figures ("underdetection/underreporting"). Depending on the pathogen, the data situation often varies: for salmonella, for example, data are available from Europe-wide baseline studies, surveillance and control programs. The decrease in salmonellosis cases is an effect of measures implemented on the basis of these data. Toxoplasmosis, on the other hand, is not reportable, although new scientific evidence suggests a link with food. All of these factors must be considered when assessing the true public health significance of a disease.

Implementation

In accordance with the provisions of the Epidemic Diseases Act, the locally competent district administrative authorities must, through the public health officers at their disposal, immediately initiate the surveys and investigations required to identify the disease and the source of infection in the event of any report or suspicion of the occurrence of a notifiable disease - and thus also in the case of foodborne outbreaks. In addition, the Zoonoses Act 2005 obliges the respective competent authorities to investigate foodborne disease outbreaks and, as far as possible, to conduct appropriate epidemiological and microbiological investigations in the process.

In doing so, the authorities have the option to call in experts. Simply stepping up untargeted food sampling has repeatedly proven to be ineffective in the past. In many outbreaks, the causal food (or the affected contaminated batch of the causal product) is no longer available for microbiological investigations at the time of the surveys.

In these cases, an epidemiological study can provide insights that enable preventive measures to be taken to avoid similar incidents in the future. The lessons learned from successfully cleared national and international outbreaks in recent years have put the necessity and usefulness of epidemiological clarifications beyond question.

Theme Report

Many authorities and institutions from different disciplines are involved in the monitoring of the food chain. Due to the complexity and the partly different objectives, a comprehensive, joint consideration is absolutely necessary. The 4th report in the AGES Wissen Aktuell series, "Foodborne Infectious Diseases", provides this overview. It also describes the causes that can lead to contamination of animal foodstuffs with certain pathogens and the measures that can be taken to reduce them by both producers and consumers.

In Austria, around 8,000 foodborne illnesses are recorded in the national epidemiological reporting system (EMS) every year. According to the WHO definition, foodborne infectious diseases are "diseases of an infectious or toxic nature that are actually or probably attributable to the consumption of food or water." In total, more than 250 pathogens and toxins are known to cause such diseases. This report is limited to 20 pathogens that are of concern in Austria (Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, EHEC/VTEC, Listeria, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibriones, Yersinia, Noroviruses, rotaviruses, sapoviruses, hepatitis viruses, Cryptosporidium parvum, Toxoplasma gondii, Cyclospora cayetanensis, Giardia and the toxin producers Staphyloccus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens). Pathogens that are virtually absent in Austria or only occur as travel diseases were not taken into account.

Last updated: 04.09.2024

automatically translated